During a brilliantly informative lecture at the RSC’s Big Director’s Weekend last month, Rob Swain (Programme Director for Birkbeck’s MFA Directing course) advised us on the first reading of a script. Read it free of all pretences and without making notes, overthinking or planning, he said. He admitted the challenge in this; directors and creatives naturally want to start imagining the world of the play and how it would be conveyed. However, Swain’s point was that we ought to sit and read straight through, uninterrupted in order to receive the play for the first time as an audience will hear it for the first time. Never again, he warned, after that first reading, will you be able to hear it afresh. And first impressions do count in theatre. Very much so. For first impressions in theatre are often, also, last impressions. And when all the elements of an exceptional play come together, they have the potential to make lasting impressions too.

Simon Stephens

So, having marvelled at numerous Simon Stephens plays, I decided to pick up one I hadn’t yet read and to follow Swain’s directive. I knew that Sea Wall has been critically acclaimed for a recent revival (I don’t have the luxury of being able to get to half the things I’d love to see over in London) and I had recently read Lyn Gardner’s column on the value of short plays. This, I thought, would be the perfect play to trial the exercise.

So, I sat and read.

Swain’s follow up instruction was to reflect on my initial reaction to the reading: the potential first reaction that an audience would experience on receiving the same information.

*Spoiler alert* If you haven’t read the play, it’s 9 pages long and worth stopping and doing so now. (It’s available online via a very easy search).

The following details my responses while reading but recorded after completing the read. Details about the play may be referenced.

Response 1/ You can’t stop your mind from wandering. My mind, although attempting to focus solely on the story Alex was telling, slid into the age-old question over monologues. How long can you expect an audience to sit and listen to a monologue for? Especially a monologue where the playwright (“always honour the playwright’s intentions” said every drama teacher in the land) requests a bare stage and natural light. A monologue that’s well formed but where, let’s face it, not a lot happens.

Response 2/ Two thirds of the way in, the Director in me was itching to work with an actor to really explore the naturalistic dialogue that Stephens crafts so effortlessly, tripping into tangents, ebbing and flowing between topics, like the waves lapping the sand, and elaborating on randomly inconsequential details. However, I knew that this was the reaction of my inner directing-geek, hungry to chew on some gentle, unsuspecting prose. Whereas, my aforementioned wandering mind was well aware that the direction would need something special to keep the audience engaged. That is, unless the last three pages had something different on offer to, say, stir things up…

Then WHAM! Response 3/ Forget directing. Forget anything. How was I going to sleep tonight after reading that? How could I rest easy with an overactive imagination and my own daughter lying asleep in the next room? How could I possibly consider directing this when the thought of it happening makes me feel sick? Fills me with dread. Touches a nerve way too close to home. How could you advertise this production to an audience without giving away what happens? Because Swain was right. This. This is how the audience feel on first encounter and this is what the director is responsible for: the creation and preservation of this immediate, unexpected response. I really hope you stopped and read the play so you know what I’m talking about.

A lesson from my own drama teacher sprung to mind: you cannot play Juliet as a tragic heroine. Juliet is a young girl in love who does not know her fate. As an actress, you need to let her live in the moment, blissfully unaware of what’s to come.

This advice struck me for the poignancy of its severe opposition to Alex’s tale. Alex confronts the audience directly to tell them his story. The very raw story of what happened to him, three weeks before. There is no hiding from his fate. His fate is the beginning, middle, end and reason for the story. The important factor in his telling of the story is that, while he knows the outcome, the audience do not. Unless they are returning for a second time and, thus, filled with the dread of knowing what will happen and that nobody can stop it. And therein lies the importance of Swain’s first reading, in parallel to Alex’s discovery of the Sea Wall… Once you’ve seen it, once you know, you can’t un-imagine it or deny its existence. Your perspective is tainted.

So, now I’m ready for a re-read with all the things I now know in mind. It will change the way I receive every word. I’m not even sure if I can handle this.

What a gloriously brilliant, harrowingly difficult and clever, clever script.

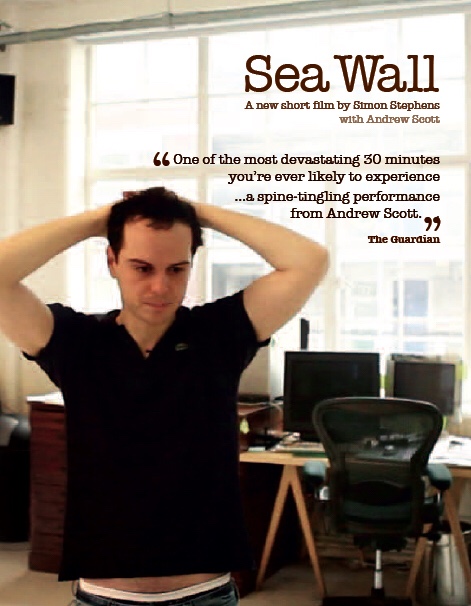

I have since read this review of the revival, which sums up the stunning performance. Now to find that downloadable recording!

‘Sea Wall’ is one of the best monologues I’ve read – I sadly didn’t have the chance to see it on stage, but I find it easy to imagine with Andrew Scott as Alex!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely. I’ve read that Stephens wrote it for him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d read that too – I don’t know if you’ve seen them, but there’s a couple of great interviews with Stephens and Scott on Youtube about ‘Sea Wall’, which are well worth a watch

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic. I will take a look – thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a really interesting post, Ginny – it would be lovely to read some more script reading exercises, because your directing and technical experience brings an interesting aspect to it. I’ve not read Sea Wall, but obviously it’s been in the news a lot recently. I did see Simon Stephens talk at my university years ago though and he was great – I might have to pick it up 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Alice. I’m definitely hoping to do more. Thank you so much for reading and commenting.

LikeLike